I revealed in a meme some time ago that I wrote a paper on three adaptations of “Hamlet” for a writing course. I decided I’d post it, although the 17 page beast was much too much for a blog. And since while you read this I’ll actually be at school, read and enjoy a condensed version of the original paper.

At the height of Shakespeare’s talent (well, so most persons would say) is his 23rd play “Hamlet”. The tragedy about a Danish prince is Shakespeare’s longest play and despite not being as readily popular as his “Romeo & Juliet” it is enthusiastically accredited as his premier work. In addition to being singled out as the pinnacle of Shakespeare’s achievement, the character of Hamlet is unofficially considered to be the greatest dramatic male role – an enviable monogram. This, no doubt, accounts for the affinity that actors, directors and producers have felt in regard to the work on stage and film.

Jude Law in his Tony nominated incarnation of Hamlet

Since the beginning of contemporary cinema in the early 20th century great thought has been placed on the constituents to good adaptations of literature, both drama and otherwise. Oftentimes works have been given the informal title of “unadaptable” but more and more fearless writers have worked against these labels and attempted at adapting great works for the medium of the film. Regardless of their valour however, something is lost when a great literature piece is transferred to cinema. It does not matter how exemplary the adaptation may be on its own their usually is some inadequacy when correlated with the original piece. There is no doubt that something is always lost when a literary work in transferred to the screen, and with the high esteem of “Hamlet” there may be an additional pressure placed on persons intending to adapt. This paper aims at assessing three notable adaptations of the Bard’s crucial play. The three versions in question are Laurence Olivier’s 1948 version, Franco Zeffirelli’s 1990 versions and Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 version. These three adaptations do not represent the gamut of “Hamlet”’s treatment on cinema. However, they are often regarded as the most popular – if not best – of the lot.

To look at each piece for a mere few minutes would immediately unearth the obvious dissimilarities. From its beginning we notice the mysteriousness of Olivier’s piece. There is a potent sense of confinement as the screen is covered in an eerie mist. Olivier’s Hamlet is mostly psychological and as Hamlet feels emotionally confined the film visually matches that with its simultaneous sense of captivity. Zeffirelli’s Hamlet is the stark opposite. The man is Italian, and vibrancy is the main component here as this is a Hamlet that is above all else, particularly physical. The court is lived in and muddy and the clothes are heavy and used. Continuing this visual comparison Branagh’s version probably falls in the middle. The confinement of Olivier is absent but there is not as much exuberance as Zeffirelli’s production.

On the most aesthetic level there are certain expectations that come with a Shakespearean themed film. Costuming is not as much a requirement for a good film as it is a prospective component of period pieces, of which Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” is one. Branagh’s Hamlet does not deliver on the authenticity of its costuming. His Hamlet is an unaltered adaptation of the play, but the players are draped in garments more appropriate for an early 20th century piece. It is a minor quibble since propriety of technicalities does not improve the quality of a film; but as aforementioned it is a natural anticipation in films of a particular period. When it comes to the realism of the costumes Zeffirelli’s Hamlet is the superior of the three. The late 15th century encompassed some ostensibly superfluous clothing for the Danish and designer Maurizio Millenoti outdoes himself. From Queen Gertrude’s flowing gowns to King Claudius’ royal robes the reality of it all is striking. Although Olivier’s costumes are not anachronisms like Branagh’s the costumes are scaled down. Naturally, the black and white palette would deny us the chance of enjoying whatever vitality of colour we may discover in the different costumes which is where Zeffirelli is able to triumph. The characters are literally dragged down by their costumes; when Ophelia descends into madness her stained gown is more than just an excessive prop but a part of her very character.

The proficiency of the costumes in Zeffirelli’s adaptation is enhanced by the added authenticity of his production design. Olivier is at a disadvantage since his Hamlet occurs in 1948 where the likelihood of films being shot on location was not large; the sets of his Hamlet are obviously superficial. Unlike the 1990 version where the castles seem real and the sweeping grounds of Ellsinore are genuine, Olivier’s Hamlet is not as sweeping. This is, of course, in keeping with the psychological nature of his interpretation and is no detractor from the overall goodness of the film. In fact, the scaled down nature of his sets is in keeping with the Elizabethan theatre and its minimal props. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the sheer splendour Zeffirelli is a bit striking to some degree. Branagh’s set design is good, but what divides it from Zeffirelli is that his sets are almost spotless. This is not the Ellsinore of Zeffirelli’s mind; this is a cleaner, grander and perhaps more noble Ellsinore.

The validity of any production of Hamlet will lie in strength of the lead character. It is a role that permits each actor to do his best with. Personally I am unable to absolutely champion any of the interpretations as faultless. Certainly, perfection is an ideal; but Olivier, Gibson and Branagh each have faults – some disconcerting some less conspicuous – that detract from the positives in their performance. Branagh, who I would readily claim to be an excellent actor, boasts my least favourite of the Hamlets. With his ominous moustache and menacing movements (not to mention his obvious age) Hamlet comes across more as a disconcerting anti-hero and less of the confused prince that he is on the page. It is not that Branagh’s acting is “bad”. He is a good actor, but his entire demeanour seems unsuited for the sensitivities of our Prince of Denmark. There is a sense that he is doing much too much for a role that shouldn’t necessarily be subtle but a trifle more sympathetic. It’s more than Branagh being inadequate on his own; his relationship with Ophelia is at its worse in this production, as far as I’m concerned. The disparity in age cannot be overstressed here. Branagh is 36 and his costar Kate Winslet (playing Ophelia) is 21. It is a 17 year age difference, and one that shows. One of the softer scenes in the play, where Hamlet renounces Ophelia (“Get thee to a nunnery”) loses its profundity in the 1996 version since I am so unwilling to accept the validity of a relationship – past or present – between the two. Certainly, the two in their separate entities try but together the chemistry is just not there. Branagh is just too freakishly sinister. On it’s own as a separate entity, his performance is fair, but taking into account the character he is playing his interpretation is bewildering.

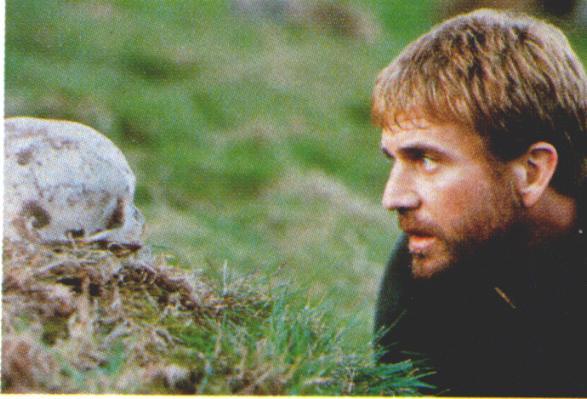

Ironically, even though I single out the 17 year gap between Branagh’s Hamlet and Opelia, Olivier’s version sports an even more disconcerting gap. At 41 Olivier is the oldest Hamlet, and at 19 Jean Simmons is the youngest Ophelia. The gap here is 22 years. Olivier is older than Hamlet should be, and it shows. But there is a svelte manner in Olivier – an eternal showman, and he looks ten years younger than he is. He would still be too old for Hamlet at 31. But old as he is, I do not doubt the romance there. His Hamlet is undoubtedly too studied, and too (psychologically) mature and though he plays the moodiness of his character effectively it’s not completely as perfect as it could be. From reading, the conflict of Hamlet is his immaturity; this is why he cannot make up his mind. Olivier’s major crutch is that his Hamlet, though broody is far from immature. The ten year gap between Mel Gibson and Helena Bonham Carter in Ziffreli’s 1990 version is the least alarming, and on a purely physical level their romance seems truest. We never are privy to Ophelia and Hamlet’s relationship in good times, but when Hamlet denounces Ophelia there is a definite spark there and I believe – completely – that there was a significant relationship between the two. Gibson is an unlikely Hamlet. He is much more physical and boisterous than either of his peers; it’s not difficult to believe that he has not studied Shakespeare like his counterparts. To his credence, when he speaks Hamlet’s lines though – they are not just mellifluous words of Shakespeare but real words of a real man. However, Gibson lacks that vital emotional connection that such a tragic character demands, and competent as he is I am never completely moved by him. Even though he suggests the youth and boisterousness of Hamlet, he fails to bring any legitimate sense of seriousness and glumness that “Hamlet” demands. Hamlet’s first appearance in the play advocate his distemper; akin to Romeo at the beginning or “Romeo & Juliet”. Olivier triumphs in highlighting this broodiness. Despite his ostensible faults I would champion Olivier as the superior Hamlet. Yes, he is too mature but from a general level taking into account the ranges of the actors Olivier is clearly the one who is closest to Shakespeare’s incarnation, and to the common reader’s perspective on Hamlet.

Whereas Olivier triumphs when it comes to the Hamlets, his Ophelia played by Jean Simmons in an Academy Award nominated role is my least favourite of the Ophelias. I will not deny that Simmons is exceedingly beautiful has moments of charm; her early scenes with Terence Morgan (playing Laertes) are a good showing of filial love. However, she seems so amateurish here she turns Ophelia – already an ostensibly weak character on the page – into a mere trifle. I am never invested in her Ophelia and though she tries hard in those final scenes when Ophelia goes mad I don’t really care. It’s strange when you consider these words of Anderson:

“Jean Simmons makes a wonderful Ophelia (she was also nominated for an Oscar), and outdoes the other three (Helena Bonham Carter, Kate Winslet, and Julia Stiles). For one thing, she’s absolutely stunning. For another, her “mad” Ophelia comes across as glassy-eyed, singsongy and muttering, rather than the screaming, crying interpretations of the recent films. It’s much more tolerable and moving. And her death scene, floating on a stream on a bed of flowers, is both simple and stunning.”

Despite having no part in either of the recent versions I cannot help taking offence to Anderson who seems to have misread the entire character of Ophelia. Certainly he’s accurate in claiming that Simmons is “stunning”. She is. Ophelia, I suppose, should be beautiful. However, he implicitly says that Bonham Carter and Winslet are facially inadequate for the role. Firstly, the proficiency of any actresses’ is more than their looks and Anderson seems to be unfairly prone to conventional beauty of Simmons, who is not definitely the most beautiful of the three. Secondly, and more importantly, what inflections does a mad person make? Certainly, dramatic license may be made since each actress will interpret Ophelia in her own rite, but even as I single out Simmons’s latter scenes as at least capable I cannot completely believe that she has descended completely into craziness. Of course, I am unaware as to the realism of any truly insane person, just as Anderson is. Neither of us can explicitly vow for how Ophelia should behave when she loses her sense, however Simmons at her best seems to be feigning (capably, albeit) her madness. Even though I believe this, I do not doubt that some may be charmed her turn, since like any character interpretation it is all subjective, and unlike Hamlet it is difficult to surmise from the play what her character is explicitly like.

Simmons’ weak Ophelia is in stark contrast to Bonham Carter’s Ophelia. With her expressive eyes Bonham Carter’s Ophelia is charming, even if not as malleable as one would expect. Her Ophelia is the obedient daughter Shakespeare demanded, but she is no simpleton. Those scenes from Act IV Scene 5 play out incredibly well on screen with her, even though they are distributed unevenly. Ophelia’s soliloquies are even more disconcerting when measured against what we have seen of her earlier. Kate Winslet’s downward spirals into madness are the most horrific though. Perhaps, due to the unabridged nature of the piece the weight of Ophelia’s destruction is even more horrific. I must consider Anderson’s disgust with the “screaming” and “crying” of the recent Ophelia’s. He is probably referring explicitly to Winslet’s Ophelia, who in the latter scenes are perpetually teary eyed. Not only is this tear-stained characterisation appropriate for her interpretation of the character – but it also lends to a fuller appreciation of the character across the interpretations. Prima facie, Winslet seems to be the best of the Ophelias, but Bonham Carter’s is my personal choice. She’s now learning her talents, but she outshines every incarnation. Whereas Kate shines when Ophelia has her important lines, Bonham Carter is more magical when she has less to say making extensive use of her face and eyes.

We may surmise that Ophelia is the female lead of Hamlet owing to her title as Hamlet’s girlfriend, but Queen Gertrude represents the central female in the play. Actually, it is Gertrude’s illicit (according to Hamlet) marriage to her dead husband’s brother that directly leads to his downward spiral into insanity. In his production Olivier secured a 27 year unknown Eileen Herlie to represent the formidable figure of Queen Gertrude. It is a casting decision that seems absurd to me. Olivier’s defenders have identified the prospective incestuous relationship between Hamlet and the Queen as added reason for highlighting a potential physical attraction between the two. Firstly, I’m sure that any son – whether he be having an unlawful relationship with her mother or not – would be despaired by her marriage to her dead husband’s brother three months hence. Olivier’s take on the plot point bears close resemblance to the Oedipus complex, but regardless of whether that interpretation is valid (or accurate) I do not find it as sufficient to warrant Herlie being fourteen years the junior of her purported son. Obviously he is attempting to imbue Gertrude with as much sexuality and sensuality as possible, but are his attempts justified? Herlie’s performance is competent, and regardless of how much she tries – her youth is highlighted, not downplayed – the realism of her fathering Hamlet seems ludicrous. Interestingly enough in the 1990 adaptation Glenn Close at 43 plays mother to Mel Gibson’s 34 year old Hamlet. It is still a strange disparity in age, but not as wide a conceit as Olivier. At 43 Close is 16 years the senior of Herlie, however Murray opines “Close brings…sexuality…to Gertrude…”. Obviously, Close’s age doesn’t detract from her ability to portray Gertrude as a figure of sensuality. The running theme of the Oedipus complex are not as overt here, but in the 1990 version the evidence of Gertrude’s (physical) love for Claudius is evident. Even if we don’t quite agree, we realise that her hasty marriage is not (just?) a calculated political movement. In addition, Herlie’s age could not have been the only way of turning Gertrude into a legitimate object of affection for the men in Hamlet. It is iniquitous to criticise the vision of the play that Olivier intended, but on a scholastic level his motives for casting such a young Gertrude seem uninspired.

Interestingly, though Branagh’s Hamlet and Kate Winslet’s Ophelia share a large age disparity, strangely enough Julie Christie – playing his mother – is age appropriate for Gertrude; not for Shakespeare’s Gertrude (who judging by Hamlet’s actual age would be in her early forties), but for Branagh’s 36 year old Hamlet. Of the three Gertrudes she’s the only one who could have actually borne their Hamlet. So with a 27 year old, a 41 year old and a 54 year old playing the Queen Gertrude the question arises as to which is superior. As with Jean Simmons’ Ophelia, Olivier’s production boasts the weakest Gertrude. It’s not that her performance is glaringly bad; it is actually quite competent in the film but measuring against the more inspired interpretation of Close and Christie, it pales. There is a particular scene where Close’s Gertrude stands out. An enraged Hamlet has (mistakenly) killed Polonius and he and his mother have a fierce battle of words. Close not only outshines her co-star (Gibson), but the layers she adds to the performance and the realism of it all is astonishing. Gertrude is a completely real woman, throughout, not the steely Queen that Herlie is. Of course, this could all be attributed to Zeffirelli’s passionate take on the story. Nonetheless, Julie Christie – though not the best – is an admirable pillar for Shakespeare’s Gertrude to hang upon. In her 54 years she is completely resplendent, and though not as uninhibited as Close she still brings a strange girlishness to her character. Whereas Close shines in that pivotal aforementioned scene, Christie’s shining moments for me come when she sees the degradation of Ophelia. Her lines are slight, but Christie is a talented facial actress and her interpretation of this scene is splendid. Nevertheless, despite Herlie not being as extraordinary as her older counterparts the Gertrudes of each adaptation seems to be competently handled.

Without uncertainty I would sincerely recommend each adaptation of Hamlet. What makes each production priceless in its own right is that they are each separate and autonomous onto themselves. This is both a positive and a negative, each production goes wrong in some entities but each also goes right in many ways. On a purely populist level Zeffirelli’s 1990 production is estimable. It’s the simplest version for someone unacquainted with Shakespeare. This is obviously owing to the dramatic licences taken, lines are abridged and characters are condensed. But the realistic nature of the piece and its excellent aesthetics make it worthy, not just for its populist appeal for its performances. Glenn Close and Helena Bonham Carter were previously mentioned as particularly exceptional, and Mel Gibson though not the best Hamlet is still good. Although not one of the main characters Ian Holm’s Polonius is excellent, he is by far the best Polonius of the three adaptations. When he coaches his son Laertes with the time worn saying “To thine own self be true” he is not just saying a line, but speaking words as if they were authentically his. The Zeffirelli version however, from a purely scholastic level, is also the one diverting most from Shakespeare. The most glaring change is the placement of the pivotal “Get thee to a nunnery” speech that Hamlet delivers to Ophelia in Act III Scene One. Zeffirelli’s version retains Polonius, Claudius and Gertrude’s plan to forge an engagement between Hamlet and Ophelia, but the aforementioned speech is moved to after the play-within-a-play. This is obviously for dramatic effect, since Hamlet’s departure, his caustic remarks and Polonius’ death could easily be regarded as a logical reason for her subsequent madness. It’s not Shakespeare’s intention, though it does work within the context of the interpretation.

Without uncertainty I would sincerely recommend each adaptation of Hamlet. What makes each production priceless in its own right is that they are each separate and autonomous onto themselves. This is both a positive and a negative, each production goes wrong in some entities but each also goes right in many ways. On a purely populist level Zeffirelli’s 1990 production is estimable. It’s the simplest version for someone unacquainted with Shakespeare. This is obviously owing to the dramatic licences taken, lines are abridged and characters are condensed. But the realistic nature of the piece and its excellent aesthetics make it worthy, not just for its populist appeal for its performances. Glenn Close and Helena Bonham Carter were previously mentioned as particularly exceptional, and Mel Gibson though not the best Hamlet is still good. Although not one of the main characters Ian Holm’s Polonius is excellent, he is by far the best Polonius of the three adaptations. When he coaches his son Laertes with the time worn saying “To thine own self be true” he is not just saying a line, but speaking words as if they were authentically his. The Zeffirelli version however, from a purely scholastic level, is also the one diverting most from Shakespeare. The most glaring change is the placement of the pivotal “Get thee to a nunnery” speech that Hamlet delivers to Ophelia in Act III Scene One. Zeffirelli’s version retains Polonius, Claudius and Gertrude’s plan to forge an engagement between Hamlet and Ophelia, but the aforementioned speech is moved to after the play-within-a-play. This is obviously for dramatic effect, since Hamlet’s departure, his caustic remarks and Polonius’ death could easily be regarded as a logical reason for her subsequent madness. It’s not Shakespeare’s intention, though it does work within the context of the interpretation. Branagh’s Hamlet is fortunate because it’s an unabridged account of Shakespeare’s work. The play within a play is relegated to a mere dumb show in both previous incarnations, but in this version it is a complete spoken word piece. Charlton Heston shines as the King within the play, and from this angle we are able to more appreciate the (prospective) guilt of Claudius. I was not as enamoured with Branagh’s Hamlet though Winslet as Ophelia and Christie as Gertude were good. I previously glossed over the visual capabilities of Branagh’s version, since compared to Zeffirelli they are second, but in all its spotlessness the film is a visual treat. Something I find interesting of this incarnation is the use of the flashback technique by Branagh, it’s an inspired notion. Though the film is an unabridged version of the play, but Branagh makes use of (voiceless) flashbacks as we see happier times in Ellsinore with Claudius seeming to lurk in the shadows, all the while plotting. These scenes are especially profound and are a nice addition to the narrative, and despite the seemingly tedious length of the film already (nearing four hours) it is never superfluous. We even see Claudius murder his brother as the ghost speaks which unlike the other two incarnations is more startling. Though I do say that I do not find Branagh’s interpretation appropriate for the role and his chemistry with Winslet to be feigned, the scene where he acknowledges her in the coffin is done so tastefully that I will single that particular moment out as handled the best of the three.

In the end though, I must single out Olivier’s 1948 production as the best of the lot. It’s ironic because I am not fond of Jean Simmons Ophelia or particularly besotted with Herlie’s Gertrude, but it seems that Agee is correct when he asserts “Any production of Hamlet stands or falls, in the long run, by the quality of its leading actor.” Olivier is the best of the Hamlets – even though he is not faultless. The thing about it is that Olivier’s Hamlet is not a true representation of Shakespeare’s play. Lines are cut, and the subplot of Fortinbras (who is plotting to overthrow Denmark) is eviscerated. Purists will call foul, but even though his is not the four hour epic that Branagh is it exists as a fulfilling incarnation of Shakespeare. A moment I appreciate greatly in his incarnation is the meeting of the ghost. In 1948 little special effects are available, but as the ghost appears in a mist and his face is almost obliterated by a helmet it is appropriately haunting and seems like such an apt way for a ghost to exist. Olivier’s talent makes up for some shortcomings in his pivotal scenes with Simmons and its possible that the mystique of the black and white palette make the film even more artistic, but as a film the talents of cinematography, and editing is utilised so effectively and despite condensation of lines, it’s still particularly profound. It is not Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” complete, but more of a compact Hamlet. Nevertheless, I feel it exists as the best of the lot, even though each is significant in their own rite.

Note: “Hamlet” is nowhere near my favourite Shakespeare play Twelfth Night, The Taming of the Shrew, Romeo & Juliet and Othello all rank above.

In the battle of Hamlet vs Hamlet vs Hamlet

It goes thus:

Hamlet (1996) B

Hamlet (1990) B+

Hamlet (1948) B+

No comments:

Post a Comment